Women, Peace And Security…Reviewing Efforts And Intentions

The 20th Anniversary Of UNSCR 1325

The United Nations has recently commemorated 20 years since the issuance of UNSCR 1325 yet efforts and intentions related to the resolution and its implications remain under review. In this article, we will shed light on our experience at the Syrian Female Journalists Network in the context of possible implications of UNSCR 1325 and our efforts in the past 2 years, we will also discuss the potential developments of these efforts.

About UNSCR 1325

The Security Council adopted resolution (S/RES/1325) on women and peace and security on 31st October 2000. The resolution reaffirms the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, peace-building, peacekeeping, humanitarian response and in post-conflict reconstruction and stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security. The resolution stresses the importance of including all the marginalized groups and often calls for unveiling any discrimination, marginalizing or omission of women based on their gender. In addition to that, it tackles ways of protection, affirmative action and justice for women.

This step comes after a long struggle by women rights defenders and non-government organizations working in the field of women, peace and security as well as the support of UN Women and 5 years since the Beijing Conference in 1995 which has dedicated a full chapter about women, peace and security.

The 1325 resolution is frequently misunderstood as a resolution that calls for the participation of women in the peace-building process because of their peaceful nature whereas the call of their inclusion is due to being largely affected by conflicts yet more often than not excluded from conflict resolution and peace-building, which is a flaw pointed out by many relevant entities. This misunderstanding might be problematic in terms of the reproduction and enhancing of stereotypical social roles. It also limits many of the workers involved in projects related to the implementation of the four pillars of UNSCR 1325 to political participation most of the time without considering the other components of the resolution which involve the role of women in conflict prevention, their contribution in peace-building and the protection of their rights during and after conflict as well as being sensitive to women’s special needs with regard to rehabilitation, reintegration into society and expression when returning home and reinstating citizenship.

20 Years And Renewed Challenges

Today and after 20 years, the imprtance of implemeting the women, peace and security agenda represented by the resolution is increasing as the map of world’s conflicts expands and critical issues features on the national and international fronts from continueous conflicts in Asia, Afria, Middle East and Latin America to climate change and its impact on human rights and women rights in particular and the COVID-19 pandemic that threatens our world today occupying an important spot in discussions at the UN’s 20th anniversary of issuing the 1325 resolution.

The UN Secretary General António Guterres said in October last month that COVID-19 is having a disproportionate negative impact on women and girls, leaving them victims of rising gender-based violence “ expressing his concern that this “ will contribute to the continued marginalization of women from political decision-making and peace processes, which damages everyone”.

Between Implications And Gaps

Going back to the resolution’s implications and mechanisms, we can notice the lack of seriousness in national and international efforts which might be due to the nature of such resolutions which doesn’t necessarily benefit political ambitions and the priorities of patriarchal international organizations. Hence, we see cosmetic efforts matched with cosmetic political representation, not to mention the victimizing, condescending discourse when talking about violence instead of treating women as actors in the development process, finding solutions and envisioning future justice, ignoring many of the female actors in other non-traditional political forms (personal, activism, civil society, development) who are often assigned exclusively to non-effective monitoring roles.

It is noteworthy to mention that the 1325 resolution is often reduced to the political representation of women which focuses on putting a number of women in decision making positions or close to such positions, falling in the trap of the ability to answer the representation question and what it carries of stereotypical societal view of women as one homogeneous group and so any form of representation should suffice. Such practices overlook women’s experiences, backgrounds and political stances.

In addition to the above, not taking participants seriously enough. Even though more activists are increasingly included but since the majority comes from privileged backgrounds it doesn’t constitute a just representation. Often the privileged women activists and politicians who are able to travel and speak in English are the ones being called upon and consulted which reinforces limited participation and the monopolization of well-known activists and politicians, a responsibility that falls on the shoulders of international organizations and its lack of sincere efforts to reach women from various backgrounds and ensure their participation.

This discussion faces one main obstacle which is the ineffectiveness of totalitarian and dictatorial systems or those using democratic tools to achieve authoritarian goals servicing the benefit of the ruling elites. Women reaching these positions by itself means nothing at all, and can’t be considered as a real measurement of women’s effectiveness.

In many cases some women are given the chance to get closer to decision-making centers and make an impact as an alternative to the failure or lack of being present in critical situations only to be excluded later on as other more serious paths are taken. Guterres pointed that out in his latest speech about the resolution 1325 saying that while women are represented in UN mediation teams, “they remain largely excluded from delegations to peace talks and negotiations”. We see that in the Syrian experience where women are excluded as actors in negotiations and ceasefire conversations to appeal to arm holders; the UN is to blame here for providing this enabling environment to exclude women.

Where is the Problem?

We can briefly say that the actual implications of the resolution do not fall under the list of priorities for international and national decision makers neither that of many of the supporters which stems from a position of not taking women issues seriously and pushing for its postponement.

The same thing applies for the UN and its organizations and councils though the United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs has mentioned the importance of sustainable, sufficient and predictable funding in this field and supporting women’s civil society work on the ground by saying that “The Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) has allocated 40 percent of its total investments to gender-responsive peacebuilding every year in recognition of the vital role women can and should play in building and sustaining peace.” DPPA has also allocated 17% of its extra-budgetary funds from its Multi-Year Appeal to projects supporting women but that doesn’t guarantee national work plans which cover the four pillars of the resolution and focuses on some at the expense of the others especially in the field of security and access-to-justice for women.

In addition, such support from the UN is tied to its recognition of the legitimacy of authorities and governments therefore contributes to the empowerment of dictatorships and corrupt governments ignoring the national plans provided by civil society actors, activists and organizations on the ground. The UN is then forced to use other channels to facilitate small funds to civil society sometimes.

In addition, such support from the UN is tied to its recognition of the legitimacy of authorities and governments therefore contributes to the empowerment of dictatorships and corrupt governments ignoring the national plans provided by civil society actors, activists and organizations on the ground. The UN is then forced to use other channels to facilitate small funds to civil society sometimes.

The funding sector remains affected by the white liberal understanding and perspective of conflict in the region. These countries suffer from a lack of national plans and financial independence to support projects due to the situation on the ground, case-in-point is Syria, where the efforts are limited to groups and actors who have access to such support and fund programmes. These programmes in turn are limited and rigid most of the time especially when they are designed by supporters in a way that includes what is called the Global South; dealing with billions of people outside of their local contexts and imposing packaged imported programmes that don’t necessarily work with the actual needs and requirements of people nor achieve any tangible results.

The Syrian Experience And SFJN’s Programme

In the Syrian context; the efforts to implement the resolution 1325 remain limited and invisible for different reasons, some of them mentioned above. In addition to the scarcity of projects; many actors unfortunately don’t care about such resolutions and might not even know they exist.

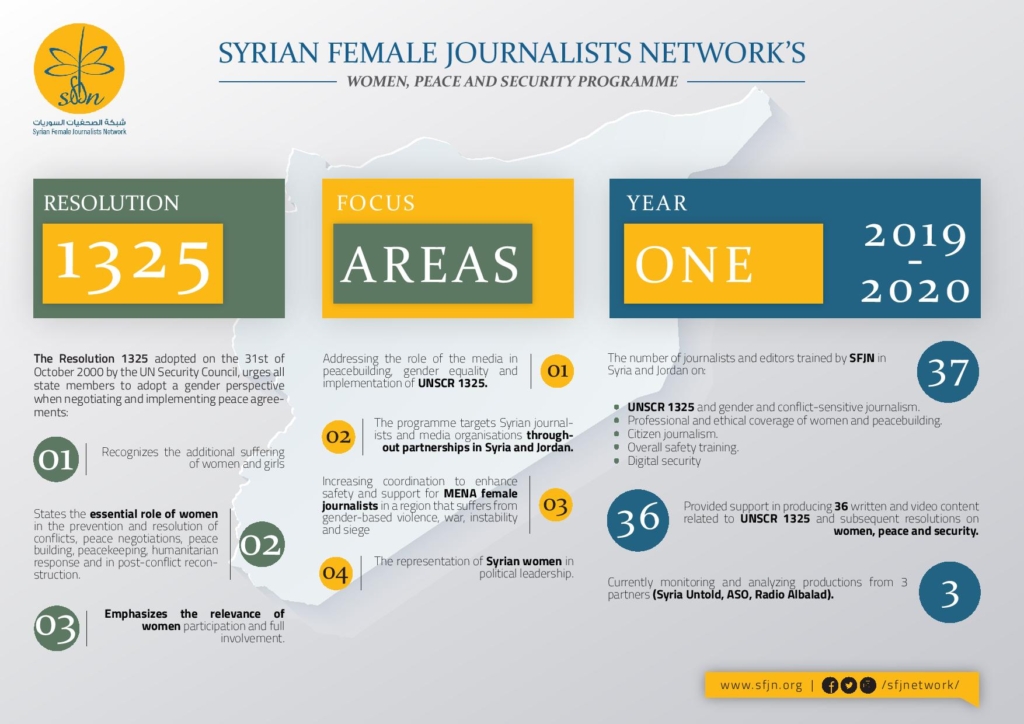

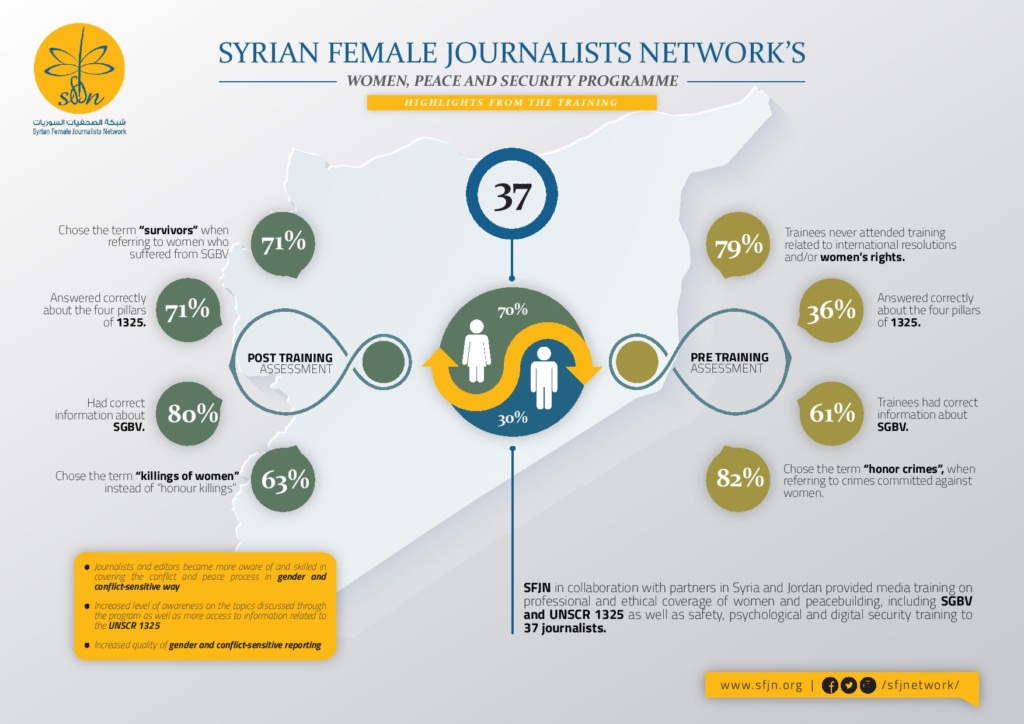

At the Syrian Female Journalists Network we have started a programme in 2019 within our field of expertise – media- to provide a background about the resolution 1325, its localization and inclusion in media production. The impact of these efforts are limited due to a number of factors related to capacity, access and difference in the level of knowledge among journalists. Not to mention the level of freedoms and the ability to deal with socially-sensitive issues in media work and how flexible the support programmes and sub-activities are.

The organization has been working with two partner organizations: Women Now and Badael and have been tapping into their expertise at different points within the program which has been divided into two stages. The first stage which focused on the training of journalists (men and women) on gender-sensitive journalism in conflict areas, the 1325 resolution as well as digital security, psychological safety and the production of materials related to the topics of the training.

Whereas the second stage focused on the evaluation and analysis of the produced materials and the future development of guidelines based on such examinations.

SFJN’s work has stemmed from its belief that media can cumulatively influence public opinion and trends. Thus, it is highly crucial that those working in the media sector understand the 1325 resolution and its gender-related concepts, and that we find ways to include it in the media discourse, which requires expanding work outside the training realm and moving to a more sustainable and effective work. The inclusion of as many media organizations and workers as possible and the creation of bigger spaces for discussion and dialogue locally and within these contexts -while taking into consideration reality- is also required for the conversation to be fruitful, scalable and with the potential to create channels of communication and feedback.

It is also equally important to impose our own vision (as actors and organizations) on supports to overcome their white-liberal and colonial views of our communities and projects implemented within them sometimes. Having a vision that is ours allows us to consider the real capacity to implement and the actual impact of these programmes without the enforcement of work agendas that don’t align with the local and regional contexts.

Finally, understanding the local context and opening the door for developing projects with local visions doesn’t negate the necessity of creating regional and international coalitions between actors and defenders of women rights for change especially in the countries of the Global South. Such coalitions will aim to make a holistic change and start the actual application of the 1325 resolution foregoing its previous rigid state that is not able to heal societies, and activating it by making a wider group of women, especially the marginalized, partners in the process and opening doors for dialogue and listening.