Can Women Become Barbers?

Can Women Become Barbers?

Journalist: Loubana Ghezlan

Translator: Anna Maria Daou

“This article was produced within the project «Empowering the Next Generation of Syrian Women Journalists» in partnership between the «Syrian Female Journalists Network» and «UntoldStories». This article was produced under the supervision of journalist Lama Rageh.”

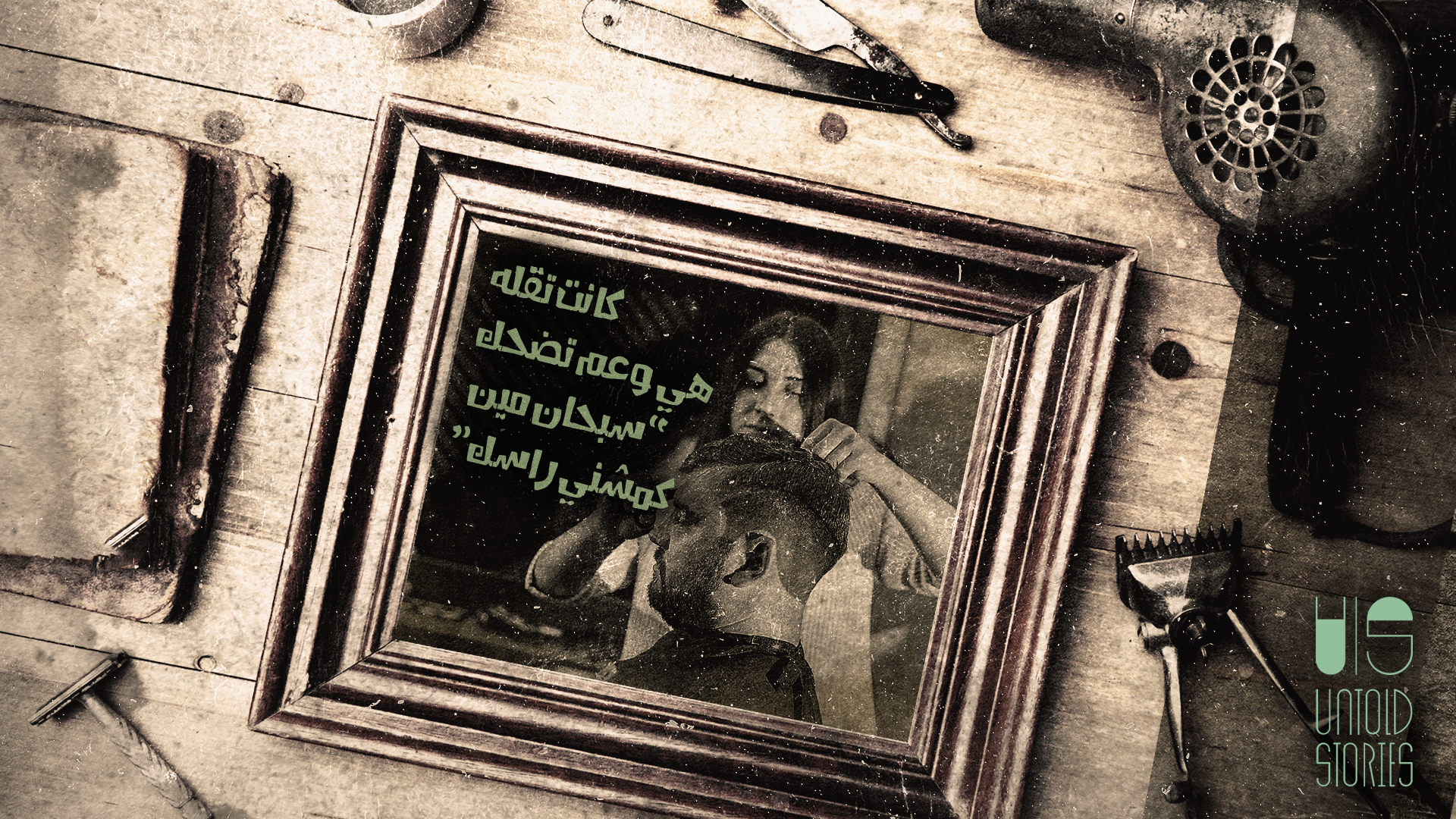

Salwa Zakzak, a Syrian writer, recalls memories of her step-mother cutting her elderly father’s hair and beard, as she constantly cared for his appearance and attire. “She used to tell him, laughing ‘Subhan mīn kams̱ẖanni rāsak’ (meaning ‘Glory be to whoever gave me the chance to shave your head!). He also used to laugh and say that he never needed a barber, that her skills and stamina were incomparable.”

“She shaved his beard every day because his hands would shake. She also did that for her father, especially during his illness. It was a truly touching scene, showing both mutual trust and affection. At that time, it was considered a privilege for a man to allow a woman to shave for him. This practice was limited to close relatives, to avoid social prejudices and judgment.”

Just like Salwa, some of us carry memories of our grandmothers and mothers grooming their spouses. However, their skills were confined to the walls of their homes and their immediate family. In other words, they never took them public, which transformed this profession into a male-dominated one in various local communities in Syria.

To write this article, 50 men (33 residing in Syria and 17 abroad) were polled to measure the degree of acceptance among them towards women working as barbers. Results showed that half the surveyed men did not have a problem with that.

In reality, the situation is quite the opposite as women wishing to become barbers still face a series of challenges. When Delara (a pseudonym for a Syrian female hairstylist residing in Turkey) was interviewed, she shared her preference of working with women. “Although this field requires more effort and skills, society cannot accept us working as barbers”, and this is what made her reluctant to pursue this career.

Farah (another pseudonym for a Syrian hairstylist residing in Lebanon) also agrees and considers that society and cultural norms affected her decision of not wanting to pursue a career as a barber. “Since we were children, they raised us on customs and traditions that reject mingling to the point of disallowing men and women to shake hands” she says. “This idea grew with us, and now it has become difficult for us to accept working in this profession.”

To better understand challenges faced by women working as, or aspiring to work as barbers in Syria, Maya Armosh, 21, working as a men’s hairstylist in Germany for the past three years, says: “I love my profession a lot, and I feel comfortable dealing with men here. However, I cannot imagine that if I return to Syria, I will be able to work with this much ease.” When asked about the reasons behind this, she answered: “It’s mainly related to the unsupportive community and the negative perception of men towards women. I am confident in my skills, but I fear both resistance and harassment from my community if I decide to open a barber shop in Syria.”

Feminist researcher Nisrine Habib clarifies the role of society and culture in pushing women away from this profession. “Patriarchal societies like ours grant men priority access to the public arena, while restricting women to specific patterns of socially-accepted professions. In most cases, they prefer women to work with women only, especially in jobs that require physical contact or proximity.”

Hani (a pseudonym), a 20-year-old barber residing in Lebanon considers that the hardest challenge any young woman wanting to work in this profession will face is “the harsh, stigmatizing looks of society. However, I believe that the younger generation might be more accepting, but those who are older will reject it and will definitely not be potential customers.”

In general, loss of social safety, due to societal rejection from close circles on one hand and societal stigma on the other, which might affect women at higher rates than men, pose significant challenges. Nisrine Habib states that when looking at the power dynamic within these societies, “the balance tilts in men’s favour, as stigma does not affect male customers who visit women barbers, but tends to affect women working in these salons.”

This decrease in social safety is exacerbated by the absence of a non-discriminatory legal environment that protects and advocates for women in cases of harassment or assault they might face while working. According to Habib, “Society, for the most part, upholds the notion that a man ‘can do no wrong’, and the law remains unable to protect women effectively.”

This is why many women prefer working as hairstylists since “women’s salons become a safe space protecting those who run them from societal violence. It’s also a place for them to express themselves in the face of male-imposed restrictions and a source of income that helps them overcome financial burdens”, Habib adds.

Economic Challenges

In addition to the dominating patriarchal social culture, women working as barbers also face economic challenges since this profession is a profitable business venture that requires managerial and financial skills to ensure its success and stability.

Economic consultant and expert in Economics and Feminist Economics, Thouraya Hijazi, emphasizes the importance of developing women’s financial and managerial skills in the face of the gender gap in accessing equal educational and employment opportunities. She believes that “it is essential to develop specialized training to empower women and align it with the needs of local markets, especially in dynamic and challenging contexts. Additionally, there’s a need to develop policies for financing small projects, which consider the cost of projects individually and avoid a uniform ceiling that grants the same budget to all projects.”

Abdul-Hadi Kahlil, a 24-year-old barber residing in Egypt, views competition positively and says: “Having women becoming barbers might relieve some of the pressure on me. However, in the long run, the grooming profession does not really depend on who is smarter or better. Hairstyling is psychological; in other words, people come to me because they feel comfortable. Therefore, everyone has their own clients.”

It is worth noting that the Syrian economy witnessed a shift in gender roles due to war and displacement. In fact, the reality imposed by the ongoing conflict in Syria has created difficult humanitarian, economic and political conditions. The majority of families lost their “traditional” breadwinners, which increased the burden on many Syrian women. Whether considered as the sole providers for their families or not, their work and participation in the labor market became necessary, either out of their desire to work and achieve their diverse economic goals, or to secure an income that helps them cover basic necessities. This is particularly crucial considering that the unemployment rate exceeded 87% in Syria, as reported in an article published by Al-Araby Al-Jadeed (The New Arab) website in March 2023.

The increasing number of women in the labor market shattered a number of patterns, especially in fields that were traditionally reserved for men, or were considered challenging. According to a report published by Radio Rozana, we now see many women working in traditional professions like sewing, agriculture, and hairstyling as well as others that were not traditionally theirs like cash for work projects, electrical repairs, mobile maintenance, truck driving, car washes, plumbing, and quarries.

Men working as women’s hairstylists is acceptable

Generally, it can be said that patriarchal societies frown upon close interactions between men and women; however, men working as women’s hairstylists do not face the same level of rejection that women working as barbers encounter. To explain this contradiction, Nisrine Habib explains that “societies which consider men as the breadwinners might justify them working in any profession that provides them with a good income, especially since the field of hairstyling is broader, more attractive, and higher-paying.” In addition, privileges granted to men in these societies allow physical contact with women, especially as professionals, which opens up various opportunities in the public space. In case women experience incidents of assault or harassment within a hair salon run by men, the hairstylist often receives social cover because of his role as a provider, while the stigma is directed towards women who choose to visit a male hairstylist rather than a female one.

Within this context, 50 women (22 residing in Syria and 28 abroad) were polled to measure the degree of acceptance among them towards men working as hairstylists. Two-thirds of the polled women had no problem with that and did not object to visiting hair salons with male staff.

Habib comments on that as follows: “those who set international standards of beauty for both women and men are mostly men. Therefore, in addition to experience and proficiency necessary for success in any profession, a male hairstylist has an advantage over his female counterpart just because he is a man. In other words, he is a main partner in defining those standards of beauty for women and shaping them through his own work. Therefore, female clients seek men’s advice and opinion because they consider them as a reference to the taste of the general male population.”

In fact, it can be said that men set the standards of beauty in many of our societies. Therefore, women working as barbers face the challenge of their clients accepting the idea of having their appearance, and their masculinity, defined by and worked on by women, especially that those general beauty criteria are set by men. In other words, local communities have, most often than not, valued the taste of men, and given more importance to their opinions in beauty standards set for women. However, to this day, many men still reject the idea of women intervening in setting their standards of beauty.

The necessity of breaking professional stereotypes

Salwa Zakzak remembers a friend who had a dream of opening and managing a barber shop. Unfortunately, her friend passed away recently without fulfilling her dream due to societal rejection of women choosing certain professions that are traditionally considered “exclusively male.”

Although society’s perception often remains unchanged towards women in the professional field, and acceptance is still subject to current circumstances, Thouraya Hijazi believes that working women today can have a positive impact on the moral and cultural framework for the participation of women in the labor market in the long run.

Last but not least, Nisrine Habib expressed her hope that the feminist revolt will reach a stage where beauty standards become individual and self-determined regardless of one’s sex. She also envisions a future where men and women receive equal job opportunities and conditions, and are judged solely on their experience and competency.