The Path to Climate Justice Starts Here

The Path to Climate Justice Starts Here

Syrian Refugee Women in Lebanon Amid Climate Change

Journalist: Walaa Saleh

Translator: Diana Abbany

“This article was produced within the project «Empowering the Next Generation of Syrian Women Journalists» in partnership between the «Syrian Female Journalists Network» and «UntoldStories». This article was produced under the supervision of journalist Maisa Salih.”

No one could mistake her voice as it gradually transformed over the years into a weary, husky voice, with difficulty breathing while talking for a long time. During our conversation with Reem, a 40-years-old Syrian refugee residing in Lebanon and a mother of three, we had to pause several times over her frequent coughing and continuous wheezing, especially when she revisits memories of her hometown, Homs. She recounts the series of displacements from one Syrian province to another, and the ongoing destruction that eventually drove her to seek refuge in Lebanon.

Back in Syria, Reem was a teacher. But in the host country, together with her husband, she works for a civil society organization, earning a combined salary not exceeding 300 US dollars.

Residing in a small, poorly ventilated house without any sunlight, its walls eroded and mould as a result of humidity, Reem lives with her small family. All these factors have led to respiratory illnesses. F

The Nature’s Rage

Recent headlines about fires in Hawaii, Canada, Algeria, and Tunisia, floods in various regions worldwide, drought in Africa and Iraq, and deadly heatwaves in Europe have begun to capture global attention. In the South West Asia and North Africa, environmental disasters were often overlooked or not even considered for years, due to various reasons including the preoccupation of some societies, like in Syria and Lebanon with more visible and bloody conflicts and wars, as well as the struggle of hardworking people to secure a livelihood amid economic collapse. These headlines have now started to dominate news bulletins even in Syria.

The World Health Organization expects that climate change, between now and 2050, will cause around 250,000 deaths annually due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress. In his book “The Meaning of Revolution in a Time of Ecological Crisis,” Martin Empson discusses how severely oppressed groups are severely affected by climate change when living in areas more vulnerable to climate-related impacts. These unequal effects result from the historical development of global capitalism.

According to the latest updates from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the estimated number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon is 795,322, with 69% of them living without the ability to secure the minimum survival expenses, known as the Survival and Minimum Expenditure Basket.

To comprehend this disparity highlighted by Empson deeply, it is essential to observe and analyze how capitalism, mainly responsible for climate change, can intersect with the ecosystem in the context of conflicts and wars, for example with asylum. Specifically, in the Syrian refugee community in Lebanon, where forced asylum imposes a complete lifestyle in which class interacts with the ecosystem, considering everything the latter entails in terms of resources, soil, energy, sanitation, and food security.

As per the Fourth National Communication Report on Climate Change in Lebanon issued by the Ministry of Environment in 2023, there has been a decline in rainfall between 1950 and 2020 at an average rate of 0.53 mm per decade. It is also expected that there will be a decrease in rainfall in Lebanon by 10% by the end of the current century. Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment data indicates an increase in the annual temperature by 1.6 degrees Celsius over a seventy-year period from 1950 to 2020. Based on this, the expected scenarios predict an increase in the temperature from 1.6 to 2.2 by 2050. Between 2050 and 2100, it is expected that the average temperature will increase by about 4.4 degrees Celsius, particularly in the summer and autumn seasons, especially in the Bekaa Valley and most coastal areas.

Walking under the Deadly Sun

Reem relies on water from the government water network for daily use. She hears rumours that it is polluted. However, purchasing sanitized water is reserved in case she was stricken by Renal colic, a condition she has been coping with for five years. The high cost of living and her efforts to meet essential needs while arranging her priorities, make sanitized water a non-priority in Reem’s economic situation.

Reem has been suffering from sinusitis and nasal polyps for years, but her health condition worsened with the recent rise in temperatures. In her tired voice, she says: “During my daily journey to work, amid rising temperatures, I walk on foot from my home to the crossroads for about seven minutes to catch a bus. I don’t reach my workplace directly; I walk for additional minutes until I get there. At work, I have to expose myself to the sun for about two hours daily, and the same on the way back. Honestly, I cannot afford the cost of transportation, but, on the other hand, these polyps grow, so I have to breathe air through my mouth, which is mostly polluted, causing severe and continuous coughing, ultimately leading to my uterine prolapse.”

Since the forced displacement operations peaked last April, her husband no longer goes to work. “I worked then intensively. I couldn’t take a leave for treatment. Therefore, I increased my working hours, exposing myself to the sun more, significantly worsening my health.”

Gynecologist Ramia Masto confirms a connection between coughing and uterine prolapse. “Coughing puts pressure on the internal organs, and its impact can sometimes be greater than the pressure from carrying heavy weights. However, coughing is not considered a primary cause of uterine prolapse, but it may cause an increase in the degree of prolapse.” The doctor also pointed out that, without treatment, complications may occur, such as ulcers and infections in the cervix, vaginal wall, in addition to urinary tract infections or disruptions in sexual relations.

In the case of Syrian refugees, who constitute a significant part of the working class in Lebanon, Syrian refugee women are on the front lines facing environmental disasters and adapting to their impacts, like rising temperatures, scarce water resources, pollution, and food insecurity. They are also compelled to meet their social roles as women, such as childbirth, childcare, and household management.

What can be emphasized here is that Syrian refugee women in Lebanon face challenging conditions as a result of intentional marginalization by the authorities. In Reem’s case, for example, her inability to take paid leave for medical treatment, the exploitation of her work capabilities for meagre wages, and the decline in her health due to prolonged walking and extensive sun exposure indicate legal marginalization. This includes the deprivation of a label law that ensures health insurance, coupled with the violence of state institutions and their persecution of refugees. Climate justice thus recognizes and acknowledges the social and economic impacts of climate change on marginalized groups, which are undeniably unequal. In this context, we mention the Lebanese Ministry of Labor’s plan to “combat illegal foreign labor,” restricting Syrian work to specific sectors, such as agriculture and construction, and placing bureaucratic obstacles in obtaining work permits- a fundamental requirement for work. Added to this is the difficulty of obtaining valid residence permits on Lebanese territory.

The violence resulting from climate change extends beyond the direct effects mentioned above. Numerous studies have confirmed a close link between climate change and gender-based violence. Water and food scarcity can lead to societal conflicts over resources, contributing to increased violent behaviours by some men. In the history of environmental disasters, women have been fourteen times more likely to be injured or killed compared to men. Studies have shown that, in disasters resulting from climate change, women often faced domestic violence, evident in partner abuse. For instance, an analysis of data from 84,000 women across 19 demographic and health surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa reveals that women residing in regions experiencing severe drought conditions are at heightened risk of encountering physical and sexual partner violence.

Living in a Nylon Bag

Measuring only three meters by two, the tent has a small ventilation opening. Its entrance leads to a large pit where sewage water flows, merely a meter away. Eight years have passed without any improvement in the tent’s condition or its foundation. Wear is the most accurate term to describe its current state. The kitchen is adjacent to the bathroom, sharing a common space. This space is separated from her tent by a plastic sheeting (“shader”), meaning that sewage pits are also near her living area, which is the general situation in the camp.

From the Qalamoun Mountains, 54-years-old Amal (a self-chosen pseudonym) carried her child to Arsal in the Lebanese district of Baalbek due to the ongoing conflict in Qalamoun at that time. All she could think about was her child and ensuring their survival. She rented a room with her savings from the gold jewellery she brought from Syria, then started knitting wool (crochet) and selling its products for a living. According to Amal, her goal was not to settle in Lebanon as a refugee; she wanted to return to Qalamoun, to her land occupied by the Lebanese Hezbollah. On her way back to Syria, she was arrested by the Syrian regime. “I wanted to return so that my child could complete his education,” she says. “But when I reached the Syrian border, I was arrested due to name similarities and remained detained in a security branch in Damascus for about three and a half months. After that, I was released, deciding to return to Lebanon.”

Upon her return to Lebanon, Amal couldn’t afford to rent an apartment, so she bought a used tent in Arsal. For the past eight years, this tent has been her home within a camp where hundreds of other tents lined up next to each other. Describing the space she lives in, Amal compared it to a “nylon bag.” This was a disapproving response to a question about coping with recent heat waves in the area. “There’s nothing to cool the tent. I don’t just call this place a tent; I consider it a nylon bag. There’s no electricity to run a fan. Sometimes, we can run it for a maximum of three hours a day.”

According to a UNHCR report on the “Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees” in Lebanon, 61% of Syrian housing in Baalbek-Hermel does not meet humanitarian standards.

The question of spaces for relaxation and recreation is also crucial. Camp residents in mountainous areas lack spaces to breathe and alleviate life’s stresses. While recounting her experiences with the camp, her connection to this place, the impact of climate changes, and its harshness, Amal mentioned a “grapevine” next to the camp. Here, amidst trees and greenery, she senses the humidity. It is a place for contemplation, breathing some fresh air, and finding respite in the shade of these vineyards on extremely hot days. This arouses her desire to visit whenever the often moody landowner permits.

Greetings, Oh Water

On a mountainside in barren land, where green spaces are scarce, these camps gather side by side. The exposed sewage pits run along the camp, sometimes filled, and then floating, reaching the camps. This not only causes harmful odors but has also led to outbreaks of cholera and hepatitis A among camp residents, as reported by the Shawish, the camp leader, in our interview.

This occurred after institutions concerned with emptying the sewage pits reduced the water suction percentage, and the Shawish started collecting a sum from each tent. They then emptied the pits and suctioned the water at the expense of the camp residents.

In recent years, water scarcity has worsened for the Syrian refugee community in the camps. Drinking water and water for daily use have diminished per individual due to a decision by United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to reduce water, sanitation, and hygiene services in the camps of Syrian refugees in Lebanon due to severe funding shortages. This decision was implemented from October of the previous year.

In response to this point, Sarah Qaddoura, a feminist activist, says: “When the crisis of pollution is addressed in conferences, refugees are often highlighted as the cause, not the affected. There is a tendency to blame refugees for ‘waste accumulation,’ and this discourse is strange and racist, as it absolves Lebanon entirely of environmental responsibility. How can communities lacking basic infrastructure deal with waste disposal?”

In the same context, Sarah speaks about obstacles faced by refugees in completing some projects, such as extending sewage networks or building cement rooms instead of tents. This is due to the concerns of some political groups about refugees’ “settling” in Lebanon. “Therefore,” she says, “we find these parties willing to deprive refugees of their right to live with dignity and adapt to environmental changes in a humane and sustainable way.”

“My share of water for daily use is 600 liters per month, which is not enough for cooking, washing, and bathing, especially in summer,” Amal tells Syria Untold. “The same goes for drinking water, where we get twenty liters every Monday and Thursday, and most of the time, it’s not enough, so we end up drinking from daily use water.”

Refugees struggle with limited water for drinking or daily use, making their mechanisms to adapt to water scarcity exhausting and confusing. Amal must wake up in the morning and walk in the sun to reach a water filling point, fill her water quota, and then return to her tent.

A year ago, Amal suffered a stroke in her foot and hand. She says she was being treated, but her blood pressure continues to rise, causing stress. “Even when the weather is rainy and stormy, if I don’t fill the water myself, I won’t get any. I have to do this.”

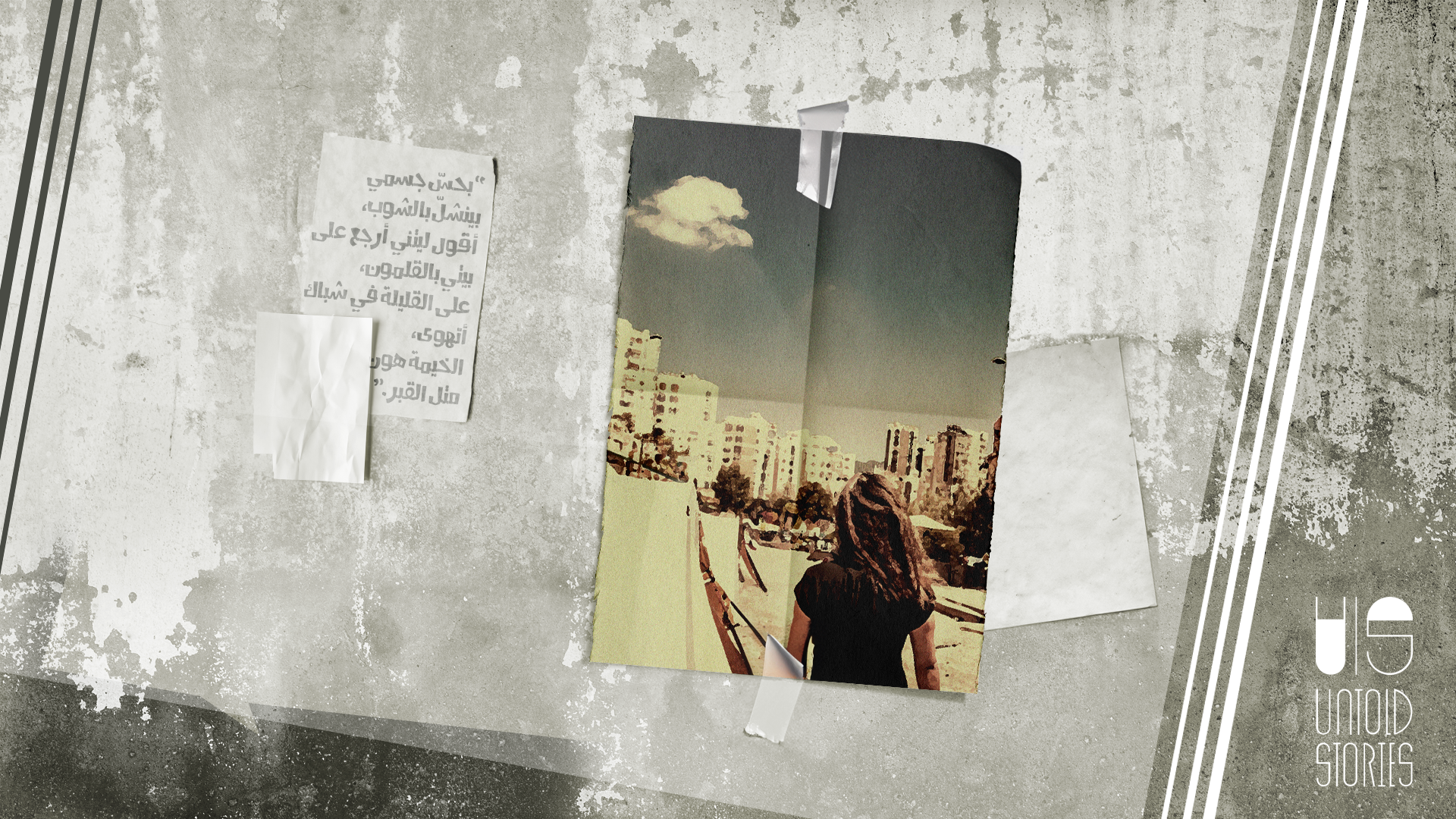

Alternative Ecological Adaptation Systems

“I feel my body paralyze in the heat. I wish I could return to my home in Qalamoun, at least there, I can find a window to get some air, unlike this tent, which feels like a grave. Since there isn’t much water, and due to the heat, I bring something to place under my feet and pour water over my head. It’s better than wasting it on the ground. I reuse it,” says Amal, who has a troubled relationship with the land. She expresses a lack of green spaces and looks to vineyards as a refuge during extreme heat. In reality, her experience of being detained in Syria, her memories of prison, verbal abuse, and witnessing the torture of other women are directly linked to her insistence on clinging to the land and residing in Lebanon, no matter how challenging the circumstances are. Despite her significant water needs, and the only barrier between her and the sun being a piece of cloth, as well as her long walks to fetch water, and carrying it on her shoulders, she has no other option than to stay, as she told me in one instance.

These challenges led us to search for alternative ecological adaptation systems to cope with climate change. We had the opportunity to meet Rosa Al-Jahmani, a Syrian environmental researcher and founder of the Grains Green organization. She holds two master’s degrees in environmental risk and management and is interested in climate change adaptation mechanisms. Rosa expressed her happiness to discuss environmental issues and climate change, given its importance, especially in light of the scarcity of resources, and to think about it in terms of marginalized groups and women. She stated, “The idea of creating tools to adapt to climate change is essential because climate changes are inevitable, given the rapid industrial cycle.”

Rosa discussed the concept of “climate injustice” in the context of our conversation about the environment, vulnerable groups, and Syrian refugee women. She explained: “Climate change is universal, but adaptation mechanisms vary from one society to another. For example, in developed countries with the ability to rely on solar panels or electric transportation instead of fuel, the consequences of these changes differ from those in developing countries or those in conflict, where these tools and possibilities are out of reach. Here we talk about climate injustice, where the impact is universal and extends beyond specific geographic scopes, but the main cause lies in major industrial countries and the consequences of fossil fuel use, along with the failure to rationalize existing resources, among other reasons.”

As for alternative environmental adaptation systems, Rosa emphasized agriculture as a crucial mechanism for achieving self-sufficiency. “I mean smart agriculture, which involves choosing seeds that fit the environment and its conditions, such as drought,” she said. “Then making the seeds adapt to changes because plants also have natural resistance to environmental factors, and there are real experiments already using low-cost irrigation methods.”

Rosa suggested promoting women’s involvement in agricultural projects because it would contribute to both self-sufficiency and the expansion of green spaces. This, in turn, could help reduce surrounding temperatures and alleviate the main contributor to global warming, carbon dioxide. Rosa also highlighted other tools for water desalination and the creation of low-cost filters, stating: “Taking into account women’s capabilities and what is available to them is crucial. That is why I emphasize the importance of agriculture.”

The Shawish we met also affirmed the possibility of farming in areas near each tent. From Rosa’s perspective, these tools or systems cannot be activated without awareness of environmental change risks. Therefore, she focused on the importance of awareness while creating alternatives. She also emphasized the need for increased studies and research in this field to raise awareness of climate change and its direct impact on our lives over the long term. “We have seen fires, floods, and rising sea levels. At the same time, there are studies and observations discussing the impact of temperatures on women’s reproductive health” she added. “Due to heatwaves in August, a delay in the menstrual cycle was noticed. There are also observations about the impact of climate change on the mental health of individuals, especially within vulnerable groups, including women, which is not isolated from their social and economic context.”

The inevitable environmental consequences loom over the Middle East, and its implications can no longer be ignored. Due to “climate injustice,” the results will have class dimensions. Today, Syrian refugees in Lebanon are living through their darkest days, where forms of oppression, persecution, and misery intersect, amidst policies of impoverishment, humiliation, social isolation, and the deprivation of their basic rights such as education, work, mobility, and health insurance. According to the women we met, factors of oppression may converge, intertwining the reality of oppression on Syrian refugees with the effects on women under such conditions, burdening them with the full weight.